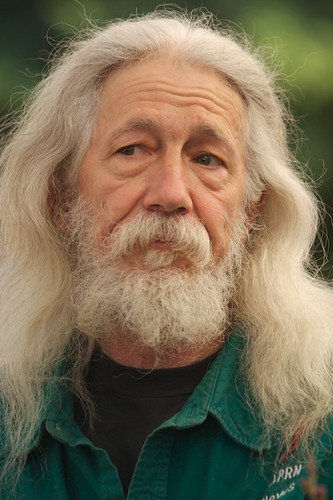

Steve Heimel

is one of those people who makes you glad you were at the right place

at the right time to connect and find common interest. We were both at KPFT-FM

in Houston, so it's not unlikely we should both have interest in things of the ear -- what the ear can understand and what someone once called "Theater

of the Mind" as being a different and more complex and subtle form of

theater than that involving visual images, such as film or Television.

So, knowing my interest in the effects sound can have on people, whether

Bernie Krause's amazing recordings of animals in the context of their environments,* or Sufi concepts explaining the use of musical tones for

spiritual purpose, or even my own rudimentary experiments with with a

guitar and echoes at Rocky Creek Canyon in Big Sur, Steve alerted me in April of this year to the fact that Stanford University was awarding Miriam Kolar the first PhD in Acoustic Archaeology at Stanford for her work on Archaeological Acoustics at Chavín De Huántar

in the Peruvian Highlands. He sent me this article he had written which

explains the principles and research better than I could.

Imagining Our Own Past and the World Beyond

Steven J. Heimel, March 31, 2012

All the way back to the Greeks and before, European culture is

rooted in worship and theater. Now a budding field of archaeology brings

us new evidence of elements of theater in ceremonial locations going

back thousands of years in both Europe and the New World.

The stones of ancient outdoor plazas rang with strange sounds that

scientists are beginning to be able to reproduce. We are beginning to

learn what an oracle sounds like.

This year for the first time the American Association for the

Advancement of Science had a session on a promising new science called

archaeoacoustics, the study of the sounds of the past. This field offers

another means of exploring the endlessly fascinating subject of the

mental processes of humans of the past. It is difficult enough to

imagine the thinking of our own grandparents, let alone historical

figures of past centuries, yet we love the mysteries of the more distant

past. Something in us wants to imagine those ways of seeing the world,

or, in this case, hearing it.

In its debut before the wider scientific world, archaeoacoustics

offered a symposium with three speakers, one of whom will soon become

the first graduate student to earn a doctorate in this field, at the

same time that her first book will be published. It's not too hard to

imagine this book making a splash. Or some thunder.

A second speaker was an engineer who has been compulsively

investigating this field because he can't help himself. His presentation

verged on poetry, with his talk of a world beyond, evoked by sound. And

the third speaker was one of the founders of the field, a professional

acoustician who makes his living controlling

noise and designing and

tuning the acoustic properties of concert halls. David Lubman had the

clout to persuade his fellow scientists that archaeoacoustics was worth a

symposium. Science can help explore the sounds of the past.

All three panelists were at pains to point out that in an era of

machinery our soundscapes have changed. The sound of motors and

overflying aircraft corrodes the acoustical world and many of us rarely

experience real soundscapes that communicate the properties of a place

and its life. We are losing our feel for them. Maybe our interest can be

re-kindled through the power of the world beyond.

There is a ritual space in the Yucatan Chichen Itza site that is

called the ball court of the gods. How could it be anything else? It's

278 feet long with 28-foot-high walls on each side, far larger than the

customary Central American ball court. Acoustician David Lubman says

those parallel walls can create all sorts of interesting auditory

echoes,

and the Maya priests must have been adept at using these properties. He

is quite comfortable calling it theater, in a respectful way. In fact,

he initially made his presentation about it at a professional conference

last year on "The Acoustics of Ancient Theatres."

So what does an oracle sound like?

Stonehenge, says investigator Steven J Waller. He has discovered that

two pipers standing a few feet apart in a field, playing the same tone,

generate an interference pattern that to a blindfolded person walking

around them, sounds like stone pillars between them and the pipers. He

has literally mapped out this interference pattern and come up with a

map of the stone circle of Stonehenge. He has also generated

interference patterns that have nodes corresponding to the vast Avebury

circle, with its 98 stones. "With the tools of modern science, we know

it is an interference pattern explained by the reinforcement and

cancellation of waves of pressure in the air. But ancient peoples must

have taken it as something from a world beyond that of our normal

senses, maybe the realm of the gods."

Waller started down his path of soundscape exploration because he was

fascinated by petroglyphs. He was surprised at what can happen to sound

at petroglyph sites. Many of them have echoes, he says. "And when you

hear an echo from a stone wall, it sounds as if it is actually coming

from behind that wall." This led him to mythology about entities that

live inside the rocks, perhaps in caves with secret entrances, "a spirit

world on the other side of an echoing wall."

Waller's outdoors experiences also got him thinking about the raw

power of some of the sounds of nature, and how people might think of

them, too, as manifesting forces of a spirit realm. Thunder and

lightning, for instance, which he links to iconography found in many

petroglyphs. Or the sound of large hooved animals stampeding. At this

point, Waller pointed to the abundance of cave art portraying animals

with hoofs. And a great many axes.

Drumming, he added, is also

portrayed.Then there is the omnipresent Kokopelli and his flute, akin to

the piper in the field. Aware of his scientific audience, Waller seemed

to be holding himself back from rhapsodizing at length on these

themes.People found it spellbinding nonetheless, and he was surrounded

by a crowd eager for more when the symposium ended

The composer R. Murray Schafer has been writing about soundscapes

for years. He's the one who coined the word. Like the

archaeoacousticians, Schafer laments the various forms of sound

pollution that deaden our senses to the auditory world around us.

Schafer writes of how puny the sounds of natural forces can make us

feel. In terms of raw power, unassisted humans can come nowhere near

generating the decibel level of a clap of thunder. But Schafer points

out that as we formed our guilds of masons and learned to build

cathedrals, we acquired the power to bring the thunder into our ritual

spaces by inventing the pipe organ. And now, he adds, with the amplified

guitar in the rock and roll arena.

It was not an archaeologist but a tour guide who first spotted a dragon

of light descending the steps of the Kukulkan pyramid at Chichen Itza at

the spring equinox. The occasion has since become a destination for new

agers, who have taken to clapping their hands rhythmically as the light

arrives along the edge of the staircase. In

1998, David Lubman

analyzed the way the sound of a handclap is reflected by the staircase.

The echo of a handclap in front of the dragon staircase is the call of

the quetzal bird. And you could clearly see it in the sonograms he

provided, and hear it in the recordings he played. Like Steven Waller,

Lubman turns to mythology for an explanation, noting the importance of

the quetzal as a messenger of the gods.

And he, too, could rhapsodize. "But you have to see the mating flight of

the male quetzal! He comes at ferocious speed straight down from very

high, his long feathers trailing behind him in waves.The colors! You can

literally see the maize fall from the heavens, its head breaking off,

revealing the grain." It's beyond imagining. To feel the power, you

would have to be there, clapping with the new agers and hearing the echo

coming back as the call of the messenger bird from inside the

pyramid.It gets better. At either end of the Chichen Itza ball court is a

temple.

A person speaking in one of those temples can be heard by a person in

the other, 540 feet away, and can also be heard by a person in the ball

court, as a "disembodied voice." Lubman says we can only imagine how

much stronger the effect was with the smoother frescoed surface the

walls would have had thousands of years ago.

Miriam Kolar of Stanford University gave the symposium an

action-packed tour of her world of the last few years, which is located

high in the Andes in Peru. It is an apparent ceremonial location at 3178

meters called Chavin de Huantar. It is about three thousand years old,

and abundant among its depictions are predatory cats from lower

elevations and psychoactive plants. This temple is the basis of her PHD

work and it could be that with the possible exception of locals, no one

living knows this temple better than Miriam Kolar. And she does not

hesitate to use locals and a great many coinvestigators in her

exploration of how this ancient world might have sounded.

Depictions by these pre-Inca people on the path of a massive labyrinth

of waterworks used to reach the location often include faces with

upturned eyes and mucus trailing from the nose. The picture is of

disorientation, at length reaching the temple to reveal an open plaza

with seating, a set of stairs and passages leading to an inner chamber.

Kolar

depicts the mission of her new field of science as to seek

"contextualized material evidence from the human past, in order to

understand ancient life...to study how sound could have been important

to ancient peoples and places." It was sensible for her to go to locals

for an understanding of what she found in the inner chamber - three

thousand year old conch shells, modified for producing sounds. If this

were a rock concert arena, the inner chamber would be the sound booth.

But in this case the instruments were not on the stage but inside the

sound booth.

What are we to make of this? David Lubman might speculate about a

priestly class seeking to mystify the crowds. But Incas were not Maya,

and Andes pre-Incas were even more removed from that bloodthirsty

civilization on the Yucatan. We might have something very different

here, and we'll have to wait for her book to find out what Miriam Kolar

speculates.She told the symposium that the sound of the labyrinth was

fascinating, with its tumbling waters, and its climbs in shaped channels

between walls, but for the most part her measurements have dealt with

the plaza and its relationship with the chamber.

There are three tunnels built between them, the central one of which

is obvious from the amphitheater. The other two flanking it have

openings that are more concealed as part of the staircases. She went to

traditional players of conch shells, called patutus, to find out what

sorts of sounds they could evoke from the instruments, and they all

traveled to the site to experiment and measure. People listening in the

plaza described the subjective effect of hearing patutus played in the

chamber as "disorienting." The players explored a number of effects, and

it was fairly easy for them to evoke the roars of big jungle cats,

among many other sounds.

The measurements this collaborative crew took at Chavin de Huantar

were exhaustive, and, as might be expected of a presentation to an

audience of scientists, were displayed in great detail. In essence, what

they show is that the comparison of the inner chamber to the sound

booth of a rock arena is apt. The mixing board used by a sound crew

always has equalizers, tuners that can amplify or diminish selected

frequencies. Kolar has found that the architecture of the passages

between the chamber do the same thing. "They perform, in effect, as

equalizers, an architectural acoustic filter system that favors sound

frequencies of the Chavin patutus and human voice."

Tanatalizingly, she goes on to say they "conducted psychoacoustic

experiments" that suggest the creators of the site built Chavin in part

"for acoustic effect, appropriate to a probable oracle center." So, the

investigators speculate, these ancients were seeking to get the world

beyond to speak. And it goes way back. Lubman points to

the Chauvet Cave's four-second dwell time for the echo of the sound of a drop of water.

Maybe we have to experience the effects to get beyond the

simplistic. Maybe we have to climb through the labyrinth. Maybe in order

to feel what would have driven people to move those enormous stones we

have to carry a certain desire through the labyrinth or along the

ancient ley lines that stretch between ancient megaliths. Or maybe we

need to start taking some measurements in our rock arenas. Perhaps there

are other modern remnants of ancient practices. I think of the totem

poles and spirit houses of the Gitxan people of the Skeena River,

reflecting an established high civilization that stretches more than a

thousand miles along the coast.

Looking at ancient monuments it is easy enough to imagine a priestly

class of some primitive society resorting to theatrical tricks in a

quest for power, but it violates the law of parsimony - these monuments

represent a far greater investment than necessary. Any mechanic of power

will tell you it takes a lot less than this to bamboozle the people.

But if we consider the way the stones were laid out in astronomical as

well as acoustical alignments, perhaps we get a clue.

There has been much speculation about the ancient shell middens of

Pinnacle Cave, a site near the tip of Africa where occupation by

creatures something like humans goes back a million years or more. As

the world glaciated, the tide pools would have retreated farther and

farther away, and some evolutionary theorists speculate that a knowledge

of the relationship between the stars and the tides might have

developed as these beings sought to keep

making the trip to get the

shellfish with their rich omega 3's to fuel the evolutionary investment

of their brains. Add to that mix the various forms that language would

have taken, such as gesture, and it is not all that hard to imagine the

roots of theater going back to Pinnacle Cave and the beginnings of what

it is to be human.

*****************

* I heartily recommend Bernie Krause's book:

The Great Animal Orchestra: Finding the Origins of Music in the World's Wild Places -- wonderful stories of things he's seen and done in places none of us will ever get to see and be.

See also:

https://ccrma.stanford.edu/groups/chavin/team.html

Chavín de Huántar Temple

Chavin de Huantar

Steve Heimel